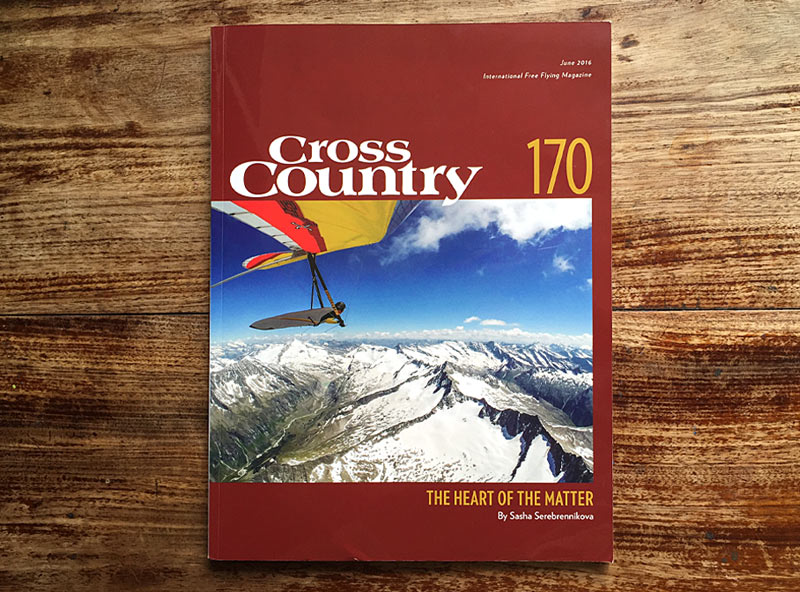

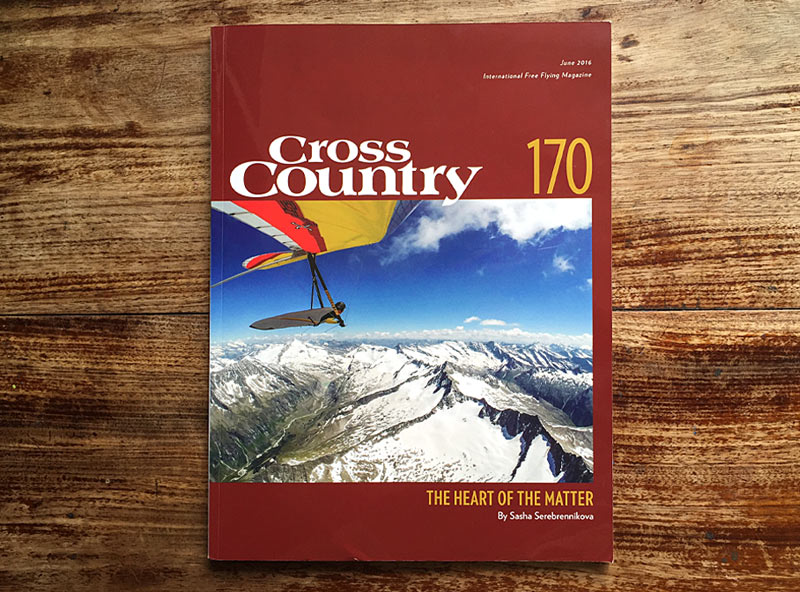

This article has already appeared in Cross Country Magazine in June 2016. I post it here now with an open access.

The presented post is about my positive experience of using heart rate monitors in flying. I have been collecting and post analyzing data for almost every flight since last 3 years. I will talk about how it helps me to control my emotional states during flying and how I use the recorded data to learn those personal traits which affect my decision making and therefore the performance.

I find it very alluring, that whatever the duration of a flight is, one should be always there dealing with himself and the on-going process. However as good as it sounds this constant need to be conscious might be rather wearing-out and stressing. Intensity consumes a lot of inner-sources and these moments can actually treacherously pull the mind into stress without one realizing it. Throuhgout the ongoing learning of hang gliding I find certain situations that cause stress and occupy my thinking. In the beginning it would be more connected to physical efforts — like non-reflex correcting of turns while towing. Later it would rather change and apply to many other cases such as strategic stagnation, when making decisions about XCountry path line and etc. The circumstances of fligh might change at times so rapidly that it also causes certain stop-overs. For me it is important to make a fast and good choice in the new situation. After my first XC season I had a feeling that there are lot of situations in my flying when I am not completely present in the moment, or say my autopilot is working instead of me. The signals for that were for instance some decisions which afterwards I couldn’t believe I really made. They were just bad. And not just afterwards, but thinking about certain situations in retrospective I thought it should have been obvious already at the moment of taking this decision, that it couldn’t be good. Those example revealed that I actually need to learn more about stress and its signals so to get hold on it.

Firstly there are two main categories of stress called acute stress and chronic stress [2]. Chronic cases might put one’s health in serious long-term peril, they belong to medical department and are treated accordingly. The other form is quite common and is met throughout daily life. Acute stress is a quickly shown response on pressures put on a person. To a given extent it is not necessarily a bad thing, often certain amount of acute stress is referred to rather freshening, uplifting and exhilarating body reactions. For instance running or any other physical activities in the row of others are also named as acute stressors. This type of stress is a short term reaction and in result, does not have enough time to do the damage that long term stress causes. The stage of acute stress which is referred to compromised decision making is called distress or anxiety. Physically instant anxiety reveals itself by three main factors – high heart rate, rapid breathing and adrenaline rush. The last in turn provokes an increase of salivary levels of alpha-amylase and cortisol hormones [7, 8]. Here is a good overview called “Understanding stress response” http://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/understanding-the-stress-response. It describes main body signals of a human exposed to a stressful situation. It is really handy if you are getting interested into subject. So measuring heart rate would clearly show whether the organism is excited or not. But hang gliding still requires physical efforts. Of course they also produce higher HR* and rapid breathing. So there is a distinction to be made between the reasons of the heart pounding. *- I’ll use the abbreviation HR for ‘heart rate’ Humans vary a lot in their ability to identify their own feelings. The article [3] “Attentional Patterns Involved in Coping Strategies in a Sport Context” from McGonagle & others gives very interesting notion that there are two types of people showing opposite patterns when coping stress. First group begins coping stress procedure by focusing on it. On contrary the second group deals it almost opposite way by trying not to think about the problem at all, as if it didn’t exist. The authors describe techniques to find out which type you are. I learned that for me becoming aware of the present emotional state is the first step to overcome the problem of irrational and wrong decisions. Because if I know that I am currently stressed it automatically means I might not realize the limits. Staying calm in the air is what I do enjoy.

So I started from getting a heart rate monitor. Back then in 2013 it was a Garmin Forerunner 310XT GPS Watch. I am used to HR monitoring when jogging and climbing but I bought this new one for flying as it was able to log the 3D GPS tracks and the pulse rate altogether. I started to record the data and examine the figures during the flights. However, in the beginning I haven’t had an orderly approach to processing the information I was getting. At the same time I luckily got enrolled into my second Adventure Flying course held by Gerolf and Zhenya in Laragne. Already before I knew they were using same monitors in their masterclasses, so I was all excited to dive deeper into subject and to see what advice, ideas and interpretations of the graphs might be brought up on the table. Each flight Zhenya would give out a few instruments to monitor and record the HR data. Then all the track logs were collected and reviewed during the briefings. I got an opportunity to see what is an average pattern for most of the flights. As the participants were different age, fitness level, gender and experience it wouldn’t be a good idea to compare the data by numbers. However, examining qualitative correlations has shown that very often I overreact in certain tensed flightparts. First of all it could be seen in the moments before taking off and landing. The following dynamic plot is a good illustration for my words. It shows a common bell-shaped pattern of HR graph with my personal rather high numbers in the beginning and the end of the flight. Also notice, how rapidly the HR drops once flared and landed.

Along with some identical tendencies, all the participants could see that each one has his/her own individual peculiarities in charts. Gerolf coined the term “Heart rate fingerprints” underlining the fact that everybody has very distinctive template of reactions on extrinsic stimuli. All these little patterns were signs of excitement, stress, physically demanding parts and so on.

Now comes the main part describing what data I have collected, which in-flight situations turned out to be rather stressing and what I am doing to overcome these effects. Why to get stressed? When thinking about reasons it is not hard to come up with the most common ones. Probably all pilots would give pretty much the same list. That would be unexpected turbulences, tricky wind conditions, lack of landings, compromised take-offs, small landing fields, flying in/in front/above clouds, waves, low-saves etc. The question is to what extent each of them affects the pilot and how often. How bad he or she reacts on these triggers. Having this idea would help to rank them by their impact on flying, which in turn would help to focus on resolving stronger conflicts before others. So better self-understanding requires consecutive studying of HR data. At the same time to have the HR lines analyzable they need to be accompanied by relevant story. Otherwise it is impossible to see what caused certain spike. Good tools for that are speeds and altitude lines plotted together with pulse. Also sometimes I make a little note attached to the flight describing some spicy things like strong turbulences which can’t be seen in classical GPS tracklog. /But with the HR graph you can’t hide it, I tell you ;)/ Each time after landing, I think about mistakes made during the flight. Observing my own behavior and reactions in different environments helps me to get better. Interestingly so after I started to follow my heart reactions I found that my main beasts are not the ones that I would expect from common sense. So for me it was worth the effort to collect and post-analyze the heart rate data. It has given me more precise idea of my personal traits. In order to have more tools and information for interpreting the flying HRs I also started collecting figures taken in daily routine situations such as sleeping, sitting, walking, jogging, tough exercising. With special attention I logged a few graphs in psychologically stressful for me circumstances, such as an important conference presentation, a big argument etc. I thought these emotional contexts resemble stressful conditions in flying because they are also caused by irrational psychological reasons. Not always the scales of anxiety are matching though. Certain situations in flying might be rather life-threatening. Nevertheless in practice I learned that unsubstantiated inflated little fears are much more common than the ones that are grounded by real perils. So now when I talked so much about this data let’s have a closer look at what I learned and how I interpreted it for myself so far. I begin with the reference data, that is some numbers from the daily life. *- My father is too good to allow emotions to spill over, it always calms me down. 🙂 I assume that my lactate threshold is about 160 bpm. According to worldwide current norms all these numbers are quite decent for my age and fitness condition. There is plenty of websites providing info about preferred resting and exercising ranges. Here are two of them: http://www.topendsports.com/testing/heart-rate-resting.htm, http://www.topendsports.com/fitness/heartrate-range.htm. Now let’s have a look at the next track logs from Laragne 2013. What is good about this concrete one, it contains the heart rate data not only from the flight but also from driving up, carrying and setting-up the glider. One can easily see how HR rises up stepwise, from one stage to another. During the flight, when actually laying in the harness, the heart beats with average of 125 bpm. This is higher than just walking around. Also notice the rapid increase before landing: Next chart shows another peculiarity of mine back then — overreacting and getting nervous when getting low and searching for a lift. Once the lift was found the stress milds away. To summarise it all up these are the moments when I was showig over reaction:

bpm

Resting HR

60

Sitting around

70-80

Fast walking, rigging the glider

90-110

Jogging with 10 kmph

135-155

Tough Nordic sky with upslopes

155-170

Arguing hard with mum

150

Arguing hard with dad*

110

The launch Launch requires good technique and concentration. Along with the excitement which increases heart rate any pilot has to carry about 50 kg of gear. Clearly a light girl like me experiences rather high efforts. No wonder that all these factors sum up into dreadful numbers. To resolve this problem I made a rule for myself to wait after carrying and before running off until HR decreases to ~125-130 bpm. It doesn’t take too long but it gives me a gap of another 40 before I am in my maximum red zone. I do two things — mentally relax and use abdominal breath technique for it. In [4] you can find more about relaxation and breathing techniques. The landing This was quite surprising for me to see that there is almost no correlation between the complexity of landing and rising HR. Pretty much all the time I had it enormously too high at ~175. Hanging in the harness before or after making a decision doesn’t require physical efforts. Therefore I have classical stressful irrational reaction. The question is why would I have this pattern when my landings weren’t bad. Well perhaps not ideal all the time, some nose-in once in a while, but nothing disastrous. Whatever was the initial reason for being too emotional, I saw that my autopilot learned wrong lesson there by getting too anxious. Actually, I do like landings, I sincerely enjoy the whole process – planning a good approach, feeling the ground effect, flaring nicely – all these inalienable parts of a flight give it ultimate final. Probably there are some natural subconscious concerns about moving too close to the ground. First thing which helps me is to be aware of the situation and of my current HR. I have a rule, that once I am getting closer to the landing, I pay my special attention to the stress level by monitoring the pulse numbers. I again breath deeply, reason myself to lower the irrational anxiety and tune my mind to enjoy the moment of landing. In contrast to launch here is no room for waiting until HR decreases, which means firstly I have to work on preventing its rise and then, when it still somehow bounces up a bit, on moderating it down. Another change that I did is using a drague chute as often as possible. Although it is not directly connected, but the fact that it reduces the chances to get in troubles has its positive influence. Of course what also matters is to stay focused on improving technique of landings. It brings sensible confidence. However, once in a while, when I forget to focus, I still get these nasty 175 bpm spikes. Altogether the progress is already noticeable and this year I had not 175 but 155 on average:

Pretty much the same things as with landings,I am trying to do during the whole flight, paying attention to my personal traits. Each time I find myself close to a low-save I remind myself not to get irrationally anxious, I concentrate on breathing and being aware of the situation. In my Gramin watch I can set up the thresholds for my preffered maximum and minimum rates, so when I get out of this zone it vibrates giving me a note. That is very handy feature. I re-set the thresholds to new, lower levels once in a while. Now my borders are from 90 to 130. The bottom line is not so important, I just like to notice when I get lower than 90. It gives me a good feeling :). Overall result comes out to be promising, my average HR decreased quite significantly and stressing reactions got much milder over the last three years. These calm flights with the moments down to 85-90 bpm leave the best memories as the brain stays awake and clear!

For my flights I currently use a Bluetooth 4.0 monitor strap connected to AVIONICUS Android and iOS (coming in Nov. 2015) application. They provide full support in live tracking and post presenting the .igc tracklogs on the personal webpage, the same like mine here http://avionicus.ru/profile/Sasha/tracks.